Comparative Displays

Good day to you all. This is post 4 for the new AstroVirtual Inc. blog.

You’ve all seen the newspaper cartoons that say “find the 12 differences between these two pictures” where in one, the person is wearing a scarf, but not in the next, and her hat had a brim in one but not the other, and so on. The idea in such cartoons is that we as observers seldom notice the incidental or peripheral objects, by comparison with the main focus of the picture.

Our focus at AstroVirtual is usually the opposite. We try to highlight the central difference by putting two images side-by-side that are composed with identical criteria except for one variable. This is especially important in analyzing “Big Data” where the true importance of the variable is masked by a huge volume of data, data that is mostly irrelevant.

We will show three examples in this post of what this means, and why comparative images are vital for such analysis.

First, a simple example from nature. We all honor the seasons (well, not always. Surprisingly here in Oregon as I write this, it is snowing along with a pronounced ice storm, and three neighbors have already complained that they moved here to avoid such things).

Here’s three pictures of the same specimen Red Oak tree (Quercus rubra), near the library at Reed College in Portland. Obviously different ‘takes’ showing the excitement of spring.

Figure 1

Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra) Reed College library in background

The Red Oak, a forest native in New England, and much of the upper Midwest, is commonly grown in gardens throughout North America. This tree is about 110 years old.

Different varieties of a tree genus and species are easily displayed with pictures, a task much harder to do in words. Here are two varieties of the European Beech species, each with summer and fall color.

Figure 2

Green Beech (Fagus sylvatica) Between the Old Dorm and Kaul Auditorium at Reed College, Portland.

Figure 3

The European Beech, with multiple varieties, has been a landscaper’s favorite in Europe for centuries. There are many red-leafed versions, plus columnar and weeping forms as well.

Figure 4

Fernleaf Beech (Fagus sylvatica Asplenifolia) Southeast corner of Caffe Paradiso at Reed College, Portland, OR

Figure 5

Fernleaf Beech

(Fagus Sylvatica asplenifolia)

A medium sized, pyramidal tree when young, developing a broad spreading crown with maturity, often becoming as wide as it is tall. This one is on campus at the SE corner of Caffe Paradiso at Reed College in Portland.

Green Beech

(Fagus sylvatica)

The majestic Beech stands out—with its shiny gray bark and sturdy trunk in winter, bright green leaves emerging in mid-spring, and a majestic crown all summer. It has been described by many experts as the finest specimen tree available.

If trees might possibly intrigue you, there is a new book, the Eastmoreland Canopy, at eBay https://www.ebay.com/itm/356556584410?chn=ps&mkevt=1&mkcid=28&google_free_listing_action=view_item

Okay so trees (actually any garden subject) are classical topics for showing the value of a picture being worth 1,000 words. But AstroVirtual tools –“LOTS OF DISPLAYS” – are valuable for almost any topic you might suggest—e.g. comparing generational hairstyles, growth rates of grandchildren, or evolution of furniture in your living room—you name it!

AstroVirtual teamed up with InnovaScapes Institute https://www.innovascapesinstitute.com/ to consider how best to analyze and illustrate issues for the worldwide COVID pandemic.

The requisite database was voluminous, with a daily 20 Mbyte ingestion and computation rate. Confirmed Cases, Confirmed Deaths, and their per capita equivalents were gathered, compiled, and correlated for 3,141 USA counties, along with 196 countries.

A base-line Dashboard was composed, which included a sizable set of important fields—a data table presentation for any selected region, a time-series plot of cases and deaths, a “Top-Ten” list, a total aggregate meter for both the entire period since start and a selected date range, and importantly, a geospatial map (correctly termed a ‘choropleth’) showing a four-quadrant map for both absolute cases and deaths and per capita cases and deaths.

Dashboard Elements. https://anywhereanytime.us/covid19c/

Table 1

The date range is adjustable from one day to three years, and the countries, states, and counties are independently selectable. Every field can be expanded to full-screen with the classic Focus mode in the upper right-hand corner. Moreover, moving the mouse over any graph region (e.g. a state or county) will ‘pop-up’ a specific detailed graph for that region.

We will discuss some of these features, feature-by-feature, in future blogposts, but for today’s topic—"Comparative Display”—we will focus on two examples of Graphical Display Analysis.

Example 1 is to look at two graphs side-by-side—the Confirmed Cases for America after three months from the first major outbreak. The left map colors counties Orange, for 1,000 or more absolute cases; counties with fewer than 100 cases are White. Shades of Blue are for numbers in-between 100 and 1,000. Clearly the most cases are occurring in the heavy population areas, such as southern California, the New York to Boston corridor, and Florida, while small counties throughout middle America show a few hotspots.

The right map shows the per capita case rate for every county, with Orange indicating more than 20 cases per 100,000 residents, while White shows less than 2 cases per 100K.

Figure 6

Startling difference, would you say? The shocking news throughout America was that the news services all showed only some variant of the left picture, never a glimpse of the right.

Let me put this in context. The week ending May 1st, was the week that America soared past 1,000,000 confirmed cases, up more than 400% (from ‘only’ 200,000) in 4 weeks, Deaths were 62,667, up nearly ten fold (TEN TIMES!) in those four weeks. And the USA press, both television and newspapers, are basically showing only a variant of the picture at the left, which allowed most citizens to be somewhat comfortable, that THEY by golly, don’t live in the hotspots, and they hope their son’s girl friend or an old cousin is okay.

One out of every 16 confirmed cases has died at this point, and the major hue and cry was for governors to get rid of the ‘lockdowns’ because “we don’t have a problem HERE.”

So, what do you think? Is a picture here worth a thousand words?

So, that is the first example. How about this one, which follows somewhat directly.

Example 2 –- comparing three time periods, using the same criteria for each one. Each time period is 4 weeks, and each in terms of Confirmed Cases shows Orange counties for more than 1,000 Cases, and White for counties with less than 100 cases. The three time periods are (1) centered around Memorial Day, before undoing the lockdowns had taken effect in places; (2) after the Fourth of July celebrations, by which time most of the southern USA states had removed all lockdowns and masking requirements, and (3) the four weeks after Labor Day, which was a month after 462,000 motorcyclists showed up for ten days in Sturgis, South Dakota, a town of 20,000 people.

Figure 7

The Memorial Day choropleth – May 18, 2020 through June 15, 2020

At the end of this ‘Memorial Day’ period, America had sustained more than two million Confirmed Cases, and more than one hundred thousand COVID Deaths. This 4-week stretch, with virtually all of the country still in lockdown and masking, witnessed two-thirds of another million new cases (nearly 250% of the earlier-shown four-week period), and more than twenty-five thousand new deaths. Case Fatality rate was 4.3%; treatments were, at best, anecdotal.

Table 2

Specifically, note how few counties were actually Orange. Only 51 counties, 1.7% of America’s 3,142 counties, had a Confirmed Case-rate of 1.0%, or one resident per hundred in your county. So, in fact, while the disease was spreading widely, it wasn’t yet too likely that you knew someone who had Confirmed COVID.

Figure 8

The Mid-summer choropleth – July 20, 2020 through August 17, 2020

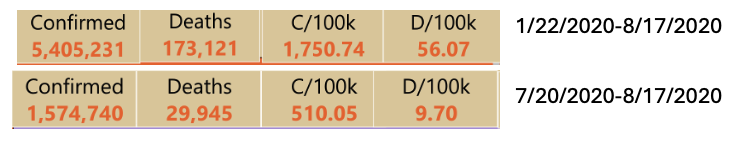

At the end of the four-week Mid-Summer period, America had sustained more than five million Confirmed Cases, and 173,121 COVID Deaths. This 4-week stretch, with much of the country no longer in lock-down, witnessed nearly 1,575,000 new cases and 30,000 new deaths. Case Fatality rate was down to 2.0%, a significant improvement, but note that the southern states, where lockdowns were lifted a month earlier than elsewhere, showed a heavy case incidence compared with other countries across America.

Table 3

This mid-summer example should have told the administration, and especially the southern state governors, that they had made a serious miscalculation. Instead of only 1.7% of America’s counties having Confirmed Case-rates of 1,000 per 100,000 residents, it moved to 10.7%, a nearly 500% increase. And virtually all of that increase was sustained in 14 southern states, who collectively had a whopping 90% of America’s counties with more than 1,000/100K (while those states only represented 46% of America’s total counties).

In fairness, geospatial maps that reveal this kind of information were likely not known or used by any of the public health officials at the time. To be sure, in Figure 8, the West Coast (notably Washington state and California where the early issues arose), but also Arizona, Idaho, and North Dakota exhibited relatively high rates. Compare the New England and Mid-Atlantic regions, though, in both Figures 7 and 8, and it is obvious that the coastal counties for those areas had learned some important lessons.

Setting aside for the moment, which regions were learning and which were steadfastly unaware, the overall picture wasn’t sanguine. There were more than twice as many new cases in this latest four-week period compared to an equivalent period two months earlier. Yes, deaths were relatively constant—the medical profession had learned some palliative treatments, none of them curative, but many helped arrest the slide to death.

Two months later, an even more startling picture emerged. In the face of these developing understandings, the South Dakota governor ignored all of the exhortations from public health officials with respect to the upcoming annual Motorcycle Rally to be held in Sturgis, South Dakota. The Trump Administration encouraged the governor to proceed—after all, it wasn’t clear that crowds matter, right? There was, to be sure, voluminous data by now from the multiple ski resort outbreaks in March, and the heavy influence of a super-spreader event at Mardi Gras, or even the concerning results in the southern states from abandoning lock-downs. Sturgis augured to bring 500,000 visitors to a 20,000 person town for ten days, the largest and longest-running event in the US in 2020 by far. Would it prove to be a COVID nightmare? Or would it be the economic boon that locals desired—after all, this is a two-week affair just once a year in a remote region long suffering from lack of jobs.

The governor, Kristi Noam, boasted that South Dakota had ‘the best COVID record of any state’ especially by comparison with the Democratic (i.e. Blue) state of New York. While the story was hyperbolic, it was true that the early outbreak in New York and New Jersey suffered very high fatality rates. This table shows the status of both Dakotas vs. New York state for the first seven months of COVID, and the three months following August 1st.

Table 4

Detail for January 22, 2020—July 31, 2020

Detail for August 1, 2020—October 31, 2020

There is a lot of information packed into this small chart. For example, note that C/100K for each of the Dakotas is less than half of New York’s in the first seven months. More importantly, the Case Fatality Rate (CFR) for each Dakota is less than ten percent of New York’s tragic 7.8% (32,232 deaths for 415,014 Cases).

Then observe that in the next three month period, the Dakotas each were roughly ten times the Case-rate per capita of New York state, rather than one-half during the earlier period. The differential now shifted by a factor of 20 times against the Dakotas. What on earth happened? The good news in this shift is that the CFR for the Dakotas improved somewhat, from an average 1.4% to 1.0%, very equivalent to the current NY results.

The bad news? The Dakotas were now #1 and #2 in the nation for Cases/100K. The next 5 states, mostly adjacent to the Dakotas, had many cyclists who’d attended the Sturgis rally. New York state was #46 for C/100K, vs. #2 for the first 7 months. South Dakota was then #36, and North Dakota #38. The time-series graph for the Dakotas is instructive as well.

Table 5

Top seven C/100K states Aug-Oct 2020

Time-Series Case and Death plots for Dakotas

Well, you can imagine the resulting Choropleth, or the Geospatial Map, for this time period. Here is the shocking plot for just four weeks after Labor Day 2020 for COVID impact.

Early Autumn 9/13/2020- 10/11/2020

Figure 9

The Early-Autumn choropleth – September 13, 2020 through October 11, 2020

Let’s reflect a bit on what these graphs show.How easy would it be to discern the specific regional challenges depicted in Figures 7 and 8 from ‘reading a spreadsheet’? Ditto for Figure 5. These are simply unable to be found by using traditional techniques.

When Noam reviewed the data prior to encouraging the Sturgis event, she and her staff could not have deduced that the upper Midwest, some 13 states with 31% of the counties, had only 6% of the countries with more than 1,000 case-rates per 100,000 residents, and a full 35% of those US counties with less than 100 case-rates. No one would’ve imagined that in four weeks shown in Figure 8, the region would go from 6% to 58% of the most infected US counties, driving counties with less than 100 case-rates to 15% from 35%.

Without the illumination of these choropleths to guide a subsequent analysis, it is highly unlikely that anyone would discover such facts. Overall (Table 6), these 4 weeks showed another 1.2 million cases and 20,000 deaths. Still appalling, but momentum, at least for now, appeared to be abating. And Washington state, California, and Arizona rates slowed.

Table 6

Yes, this is a lengthy post, but it illustrates what multiple displays can reveal. Note that, as written herein, they appear as sequential images. The real value of AstroVirtual displays is that you can put them side-by-side, or stack them, allowing for easier comparisons.

Meanwhile, just savor the value of seeing all three together at once, and then imagine how each of these maps will appear on a VERY LARGE VIRTUAL SCREEN that is 30 feet diagonal, so it fills a Virtual room more than 60 feet long, 12 feet high. When you ‘walk through this room’ traversing it with a simple mouse, you’ll truly feel IMMERSED in the scene.

Figure 10

4 weeks around Memorial Day lock-downs and masks ‘everywhere’

4 weeks mid-summer Southern states remove lockdowns

4 weeks early autumn South Dakota hosts 500K bikers

What we haven’t discussed yet in this series of AstroVirtual blogposts is that putting those images together is just the first step—in fact, each of them are then interactive and can be modified to inspect smaller regions or different times, or whatever seems most appropriate for the viewer. We’ll discuss these kinds of possibilities in succeeding posts.